A company has only one peerless role: chief executive officer. It’s the most powerful and sought-after title in business, more exciting, rewarding, and influential than any other. What the CEO controls—the company’s biggest moves—accounts for 45 percent of a company’s performance. Despite the luster of the role, serving as a CEO can be all-consuming, lonely, and stressful. Just three in five newly appointed CEOs live up to performance expectations in their first 18 months on the job. The high standards and broad expectations of directors, shareholders, customers, and employees create an environment of relentless scrutiny in which one move can dramatically make or derail an accomplished career.

For all the scrutiny of the CEO’s role, though, little is solidly understood about what CEOs really do to excel. McKinsey’s longtime leader, Marvin Bower, considered the CEO’s job so specialized that he felt executives could prepare for the post only by holding it. Many of the CEOs we’ve worked with have expressed similar views. In their experience, even asking other CEOs how to approach the job doesn’t help, because suggestions vary greatly once they go beyond high-level advice such as “set the strategy,” “shape the culture,” and “get the right team.” Perhaps that’s not surprising—industry contexts differ, as do leadership preferences—but it illustrates that fellow CEOs don’t necessarily make reliable guides.

Nor has academic and other research on the CEO’s role done much to illuminate how CEOs think and what they do to excel. For example, recent studies that detail how CEOs spend their time don’t show the difference between a good use of time and a bad one. Academic research also demonstrates that traits such as drive, resilience, and risk tolerance make CEOs more successful. This insight is helpful during a search for a new CEO, but it’s hardly one that sitting CEOs can use to improve their performance. Other research has tended to produce such findings as the observation that leaders are effective in some situations and ineffective in others—interesting, but less than instructive.

With this article, we set out to show which mindsets and practices are proven to make CEOs most effective. It is the fruit of a long-running effort to study performance data on thousands of CEOs, revisit our firsthand experience helping CEOs enhance their leadership approaches, and extract a set of empirical, broadly applicable insights on how excellent CEOs think and act. We also offer a self-assessment guide to help CEOs (and CEO watchers, such as boards of directors) determine how closely they adhere to the mindsets and practices that are closely associated with superior CEO performance. Our hope is that all CEOs, new or long-tenured, can use these tools to better apply their scarce time and energy.

A model for CEO excellence

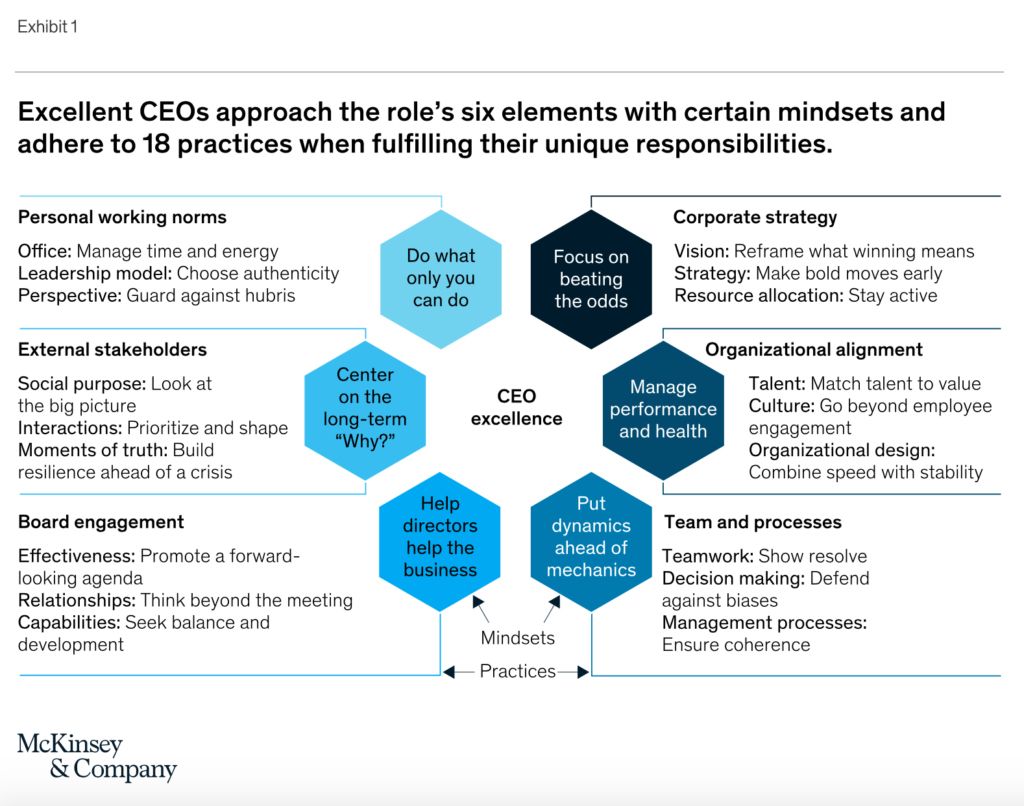

To answer the question, “What are the mindsets and practices of excellent CEOs?,” we started with the six main elements of the CEO’s job—elements touched on in virtually all literature about the role: setting the strategy, aligning the organization, leading the top team, working with the board, being the face of the company to external stakeholders, and managing one’s own time and energy. We then broke those down into 18 specific responsibilities that fall exclusively to the CEO. For example, setting a corporate strategy requires that the CEO make the final call on an overall vision, a set of strategic moves, and the allocation of capital.

Focusing on those 18 responsibilities, we conducted extensive research to determine what mindsets and practices distinguish excellent CEOs. We mined our proprietary database on CEO performance, which is the largest of its kind, containing 25 years’ worth of data on 7,800 CEOs from 3,500 public companies across 70 countries and 24 industries. We also drew on what we’ve learned from helping hundreds of CEOs to excel, from preparing for the job and transitioning into it, through navigating difficult decisions and moments of truth, to handing their responsibilities over to a successor.

The result of these efforts is a model for CEO excellence, which prescribes mindsets and practices that are especially likely to help CEOs succeed at their particular duties (Exhibit 1). What follows is a detailed look at these mindsets and practices. Although our findings are most relevant to CEOs of large public companies, owing to our research base, many will also apply to CEOs of other bodies, including private companies, public-sector organizations, and not-for-profit institutions.

Corporate strategy: Focus on beating the odds

It’s incumbent on the leader to set the direction for the company—to have a plan in the face of uncertainty. One way that CEOs try to reduce strategic uncertainty is to focus on options with the firmest business cases. Research shows, however, that this approach delivers another sort of outcome: the dreaded “hockey stick” effect, consisting of a projected dip in next year’s budget, followed by a promise of success, which never occurs. A more realistic approach recognizes that 10 percent of companies create 90 percent of the total economic profit (profit after subtracting the cost of capital), and that only one in 12 companies moves from being an average performer to a top-quintile performer over a ten-year period. The odds of making the jump from average to outstanding might be long, but CEOs can greatly increase the probability of beating those odds by adhering to these practices:

Vision: Reframe what winning means. The CEO is the ultimate decision maker when it comes to setting a company’s vision (where do we want to be in five, ten, or 15 years?). Good CEOs do this by considering their mandate and expectations (from the board, investors, employees, and other stakeholders), the relative strengths and purpose of their company, a clear understanding of what enables the business to generate value, opportunities and trends in the marketplace, and their personal aspirations and values. The best go one step further and reframe the reference point for success. For example, instead of a manufacturer aspiring to be number one in the industry, the CEO can broaden the objective to be in the top quartile among all industrials. Such a reframing acknowledges that companies compete for talent, capital, and influence on a bigger stage than their industry. It casts key performance measures such as margin, cash flow, and organizational health in a different light, thereby cutting through the biases and social dynamics that can lead to complacency.

Strategy: Make bold moves early. According to McKinsey research, five bold strategic moves best correlate with success: resource reallocation; programmatic mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures; capital expenditure; productivity improvements; and differentiation improvements (the latter three measured relative to a company’s industry). To move “boldly” is to shift at least 30 percent more than the industry median. Making one or two bold moves more than doubles the likelihood of rising from the middle quintiles of economic profit to the top quintile, and making three or more bold moves makes such a rise six times more likely. Furthermore, CEOs who make these moves earlier in their tenure outperform those who move later, and those who do so multiple times in their tenure avoid an otherwise common decline in performance. Not surprisingly, data also show that externally hired CEOs are more likely to move with boldness and speed than those promoted from within an organization. CEOs who are promoted from internal roles should explicitly ask and answer the question, “What would an outsider do?” as they determine their strategic moves.

Resource allocation: Stay active. Resource reallocation isn’t just a bold strategic move on its own; it’s also an essential enabler of the other strategic moves. Companies that reallocate more than 50 percent of their capital expenditures among business units over ten years create 50 percent more value than companies that reallocate more slowly. The benefit of this approach might seem obvious, yet a third of companies reallocate a mere 1 percent of their capital from year to year. Furthermore, research using our CEO database found that the top decile of high performing CEOs are 35 percent more likely to dynamically reallocate capital than average performers. To ensure that resources are swiftly reallocated to where they will deliver the most value rather than spread thinly across businesses and operations, excellent CEOs institute an ongoing (not annual) stage-gate process. Such a process takes a granular view, makes comparisons using quantitative metrics, prompts when to stop funding and when to continue it, and is backed by the CEO’s personal resolve to continually optimize the company’s allocation of resources.

Today’s guest post comes to us from Carolyn Dewar, Martin Hirt, and Scott Keller for McKinsey & Company.

Click here to read the rest of the article.

Share This Post